Part II

This is the second part of an update on the outbreaks of HPAI A(N5H1) in at least 33 dairy farms in eight states.

I am going to try to explain some very complicated matters in simple terms, so I will apologize in advance to all the cell biologists, microbiologists, virologists, anatomists, laboratory scientists and all other experts who know more than I do for my oversimplifications.

Developments

- On April 25, the FDA reported preliminary results its nationally representative commercial milk sampling study. The initial results show about 1 in 5 of the retail samples tested are quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)-positive for HPAI viral fragments, with a greater proportion of positive results coming from milk in areas with infected herds.

[Translation: I reported in Part I of this update that the avian influenza virus has been identified at high levels in the milk of infected cows. The USDA is working with dairy farms to isolate sick cows from the rest of the heard, since we still as of this time are not certain how the virus is transmitting to and potentially among cattle. Their milk is also being discarded until such time as they are fully recovered. But questions remain, including could there be infected cows that were not showing signs of illness and yet virus might be in their milk and processed for human consumption? (The answer to this question appears to be yes.) Even if that happened, the USDA and FDA had indicated that based on what we know about influenza viruses (they are heat sensitive) and what our past experience and research has taught us about the pasteurization process (highly effective at preventing the transmission of bacteria and viruses to humans) that the milk supply should be safe and so long as the milk and other dairy products were pasteurized prior to consumption, there should be little, if any, risk to the public. However, we do not have previous studies on the effectiveness of pasteurization on this particular virus, so I applaud the USDA and FDA for designing the studies to ensure that the A(H5N1) virus is not getting into the commercial milk distribution in a potentially infectious form.

To this end, the FDA sampled commercial milk products initially with a screening technology – the use of “quantitative polymerase chain reaction” tests, tests that are much more familiar to the general public now because of the COVID-19 pandemic. So, what is this test and what does it tell us?

We can identify the presence of virus or parts of virus through looking for genetic sequences that are unique or highly characteristic of that particular virus. The genetic code for a virus, for animals, and for humans is expressed in RNA (as is the case for influenza and SARS-CoV-2) or in both DNA and RNA for some other viruses, animals and humans. That genetic material is referred to as a code because it is a sequence of building blocks called nucleotides that are limited in number (and have one variation between DNA and RNA), that are assembled in a specific order and sequence. Thus, if we were to write out that sequence of nucleotides using the initials for the various nucleotides, you would get a string of letters that is the code that serves to instruct parts of the cell that read that code what building blocks (called amino acids) should be assembled in what order that will create the proteins to make new virus, such as the H5 hemagluttinin protein and the N1 neuramidinase protein. But, when we take a sample, like you likely had if you got sick and doctors were trying to decide whether you had COVID-19 (this is different from the rapid antigen home tests), we can put it in a machine that will use an enzyme called polymerase to copy the genetic sequence and each cycle it goes through, it makes more copies of that genetic sequence until such time as the probes we use looking to see if that specific sequence is in the sample can detect it. (Another name we use for this test is NAAT – nucleic acid (that’s what nucleotides are made up of) amplification test). If the test is positive, that unique or highly suggestive specific sequence of genetic material is detected, making it highly likely that virus, or at least portions of the virus, are present in the sample. If negative, it is highly unlikely that the virus is present, at least not at levels that we can detect.

The “quantitative” part of the test refers to that we can count the cycles of amplification of the genetic material that are necessary to get enough genetic material for us to detect. Therefore, a low number of cycles (we call these cycle thresholds or CT values) until a positive test means that there must have been a lot of virus present, because we didn’t have to amplify it much, whereas a high CT value means there wasn’t very much viral genetic material present because we had to repeatedly amplify it to get enough genetic sequences that we could detect it.

So, a negative test is the end of the story. We can be fairly confident that the virus is not present because we can’t find any of its genetic material. On the other hand, a positive test only means that the genetic material is detected, but doesn’t necessarily indicate that intact virus is present, or even if it is, that it is infectious. For example, imagine I was cutting vegetables and slipped with the knife and cut off a chunk of one of my fingers. I then took it to the hospital to see if they could reattach it. They decide they can’t, so they bandage me up and I go home. If they sent the chunk of my finger to the lab and did genetic sequencing test on the tissue, it would be my unique genetic sequence, but it would not be me. I would already be at home trying to gin up some sympathy from my wife.

Similarly, if there was virus in the milk at the farm when the cow was milked, but the pasteurization process inactivated all of the virus, and we tested a sample of milk from the grocery store that contained milk from that cow, the qPCR test might very well be positive because it is detecting the genetic sequence, but it is inactivated virus or viral debris.

So, if the genetic material is detected in the milk from the grocery store, how do we know whether the virus is intact and infectious? There is more than one way to answer that question, but the gold standard (best test) for an influenza virus, especially an avian influenza virus, is to inject some of that sample into eggs and see if it will grow (i.e., an infectious virus will infect cells of the egg, enter those cells, hijack the cell’s normal protein-making machinery and instruct it to drop everything and make viral proteins according to the instructions of the genetic material making up the virus’ RNA to make H5, N1 and all the other proteins necessary for new viruses, as well as the instructions as to how and in what order the proteins should be assembled so that new virus progeny can now exit the cell and infect new cells to repeat this process. If the amount of virus grows then we know it is replicating (infectious) virus; if it doesn’t, then it is not replicating and therefore not infectious.

This test takes days to weeks, but we are told that initial test results have not demonstrated infectious virus. If the cultures continue to remain negative, then that means that the pasteurization process is inactivating the virus, and the public need not worry about the safety of pasteurized milk for human consumption. Of course, all of this presumes that humans can be infected with A(H5N1) through ingestion, and we don’t know that for certain, though there is reason to be concerned that could be possible. (More on this below).

- On April 26, the FDA, together with the USDA, provided another update in which they reported that the embryonated egg viability studies (the scientific name for the tests I just described above using eggs to determine whether the detection of genetic material in pasteurized milk represents infectious virus or viral debris from the inactivation of virus through pasteurization). They indicated that all tests remain negative to date. We want to give these tests more time to be sure, but this is certainly encouraging news.

- There was more good news shared in that latest update. The FDA has also tested retail powdered infant formula and powdered milk products marketed as toddler formula. All PCR tests were negative, meaning that there was no genetic material from A(H5N1) detected, and therefore, no need for additional testing.

- Further, the CDC indicated that there have been no further human infections detected since the initial case identified in association with these dairy farm outbreaks. This is great news, however, to my knowledge the epidemiological surveillance is limited to persons presenting with illness compatible with influenza infections, including conjunctivitis at emergency rooms and hospitals, so we may be missing cases without broader testing and surveillance.

So, lots of good news supporting the likelihood that the pasteurization process does protect us from infectious A(H5N1) virus in that milk or dairy product. I use the word “supporting” instead of “proving,” simply because I am not sure that the embryonic egg viability studies have been given enough time to ensure that there is no growth.

Of course, all of this is moot if the A(H5N1) can’t infect humans through ingestion of virus either because the acidic environment of the stomach (of course, if this was the only protection from ingested virus, this would still leave some humans vulnerable due to hypochlorhydria (low levels of acid in the stomach) or achlorhydria (absent levels of hydrochloric acid in the stomach), conditions that can be caused by people taking antacids or proton pump inhibitors for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux or peptic ulcers, hypothyroidism, certain autoimmune syndromes, or those who have undergone surgical removal of the part of the stomach that produces acid such as those who underwent gastric bypass surgery for weight loss or a Whipple’s procedure for pancreatic cancer.) or because we do not have the right receptors lining our gut for the virus to attach allowing the virus to ultimately enter the cells and cause infection.

It seems strange to talk about ingesting an influenza virus and becoming infected because influenza virus has traditionally been spread by airborne or respiratory droplet transmission, and this mode of transmission (ingestion) does not occur with our usual seasonal influenza viruses. So, why the concern about humans drinking the milk of infected cows? There is mounting concern that a number of mammals that are carnivores or omnivores have been infected by scavenging and then eating the carcasses of infected birds, or possibly other infected animals, including cats (we recently have six reported cases of avian influenza infections in cats in the U.S. and all six died), dogs (for some reason that I don’t understand, but veterinarians likely do, beagles seem to be most susceptible among the dog breeds), leopards and tigers. While, it seems likely that ingestion is the route of infection, we cannot rule out that the virus was inhaled by the mammal during the process of eating the dead bird. There are also animal studies that demonstrate that ingestion of A(H5N1) virus can cause systemic dissemination of virus in these animals, e.g., see “Systemic Dissemination of H5N1 Influenza A Viruses in Ferrets and Hamsters after Direct Intragastric Inoculation.” https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00148-11 In this particular study, the virus was introduced directly into the stomach, bypassing the oral and nasal passages, which should eliminate the confounding risk that possibly the virus was inhaled during the process of eating.

While there are reports of people with human infections of avian influenza having conjunctivitis as the only manifestation, those who become severely ill and die have pneumonia, so there needs to be a route for the virus to get from the gut to the lungs, if ingestion is a route of transmission that can result in severe illness and death. Because there are no direct connections where virus can merely advance from cell to cell and tissue to tissue to the lungs, one would postulate that for virus to get from the gut to the lungs, it must do so either through the blood (what we would call a viremic phase in which virus enters the bloodstream and can circulate to other organs) or a lymphatic route, in other words, from the gut, to the local lymph nodes to the regional lymph nodes and ultimately into the lymphatic system.

The animal study referenced above, showed that virus could rapidly and directly infect the lymphatic system after inoculation of virus directly into the ferrets’ and hamsters’ stomachs, but in the hamster model, there was also evidence for hematogenous (by the blood) spread to the lungs. Hamsters have some particular relevance to what may happen in humans as they are susceptible to the normal seasonal influenza viruses that we get infected with, and they seem to have a similar distribution of the relevant receptors (more on this later) for the avian influenza viruses.

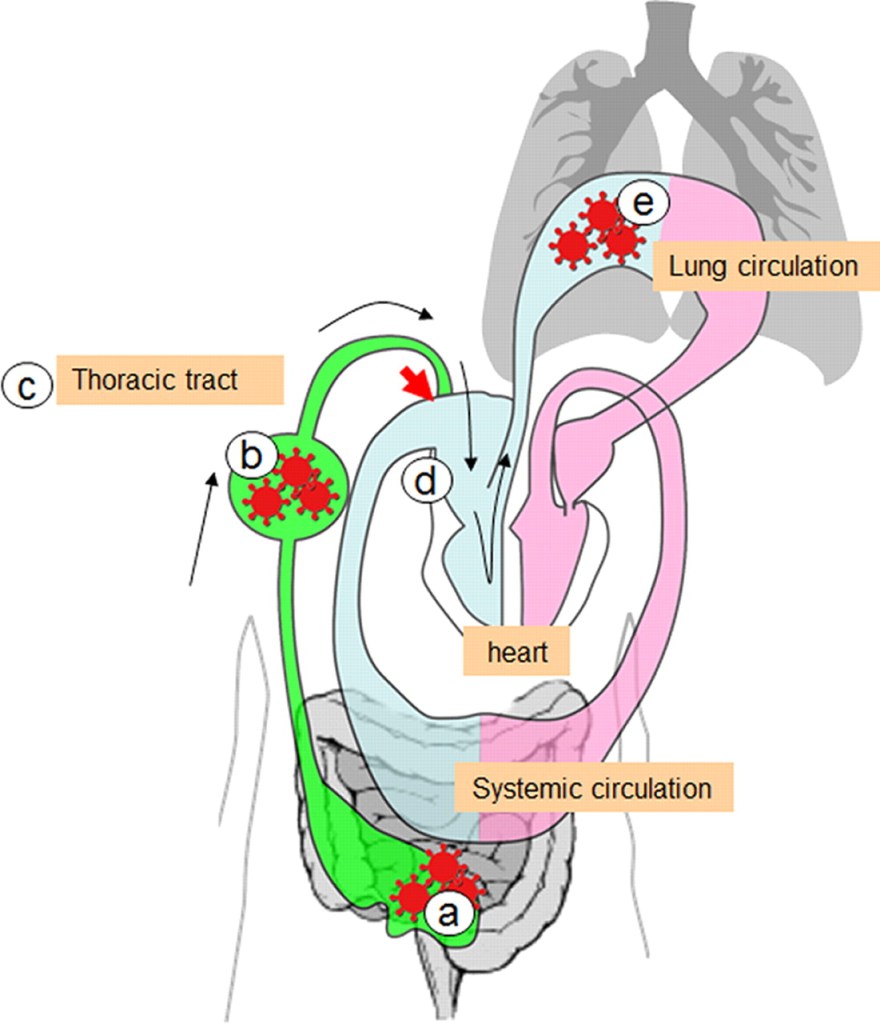

Here is an illustration from that article:

The infectious virus is represented in red. The results of the study suggest that when the animal ingests food containing infectious virus, the virus enters the stomach and travels through the animal’s digestive tract down to the intestines (represented in the picture by the letter a). Our intestines have lymph nodes within and adjacent to the intestines that help us respond to potential pathogens we might ingest. However, in this case, the virus is not contained by this first line of defense, first causing lymphadenitis (infection of the lymph nodes) and then spreading beyond these nodes into the lymphatic system (represented by the letter b in the illustration). The virus is transported through the lymphatic system into the thoracic duct which returns the lymph to the venous system and venous return to the right side of the heart (represented by the red arrow in the illustration). The right side of the heart pumps the venous blood that returns to it from all parts of the body, containing the lymphatic return from the thoracic duct, to the lungs, where the lungs oxygenate the blood that will then return to the left side of the heart to be pumped out to the body to deliver oxygen and nutrients to tissues. However, it is the pumping of the venous and lymphatic return (now containing virus that entered the body from the gut) to the lungs (represented by the letter e in the illustration) that transports the virus to the lungs and results in pneumonia.

Seasonal influenza viruses that humans are exposed to each year do not infect us in this manner, probably because the H1, H2 and H3 proteins do not tolerate the low pH (acidic) environment of our stomachs. However, it appears that H5 does tolerate this environment much better, and may explain why there may be a risk of infection from ingestion of avian influenza viruses in humans that is not characteristic of the seasonal influenza viruses we are familiar with. Obviously, more research is needed.

I will pick up on this update in Part III, because we still have much to cover. Dr. Rick Bright is a renowned virologist and immunologist who has been an influenza researcher for decades, who also served our country as the director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). He and other scientists have raised four important questions that need to be answered about these outbreaks https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2024/04/26/1247479100/bird-avian-flu-cows-cattle-milk-virus-unanswered-questions. They include:

- How widespread is the virus in dairy cattle?

- Does the milk testing positive on retail shelves contain infectious virus?

- How exactly is the virus spreading?

- What is the risk to humans as the virus keeps spreading?

I certainly don’t have the answers to these important questions, but I will continue to update the public about what we know, what we are learning, and what is happening with these outbreaks. We have a lot more to discuss in Part III of this update.

some place I read that dairy cows are fed chicken poop. was that U?

LikeLike