You may think that the title is a bit weird, but it is intentional. I am going to give a brief overview of the current understanding of Long COVID. However, I have practiced medicine long enough to understand that our knowledge about who gets certain diseases, why those individuals get the disease, what mechanisms are causing the disease manifestations and treatments for diseases evolve over decades. There are many reasons for this, but the explosion in our knowledge and understanding of immunology and genetics are two of the main ones. In fact, today, we are beginning to use a combination of genetic editing and, in some cases, the use of certain immune cells to treat cancers, and potentially even cure sickle cell disease, something that was once unimaginable by doctors practicing medicine when I started.

Let’s start with what is the definition of Long COVID. Now, you would think this is a simple question to answer – it isn’t. There is not agreement among different countries, researchers or treating physicians as to what criteria must be met for this diagnosis. We can’t even agree on the name – Long COVID, post-COVID conditions, chronic COVID, and post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) – to name just a few.

So, here is the definition that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services came up with:

“Long COVID is broadly defined as signs, symptoms, and conditions that continue or develop after initial COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 infection. The signs, symptoms, and conditions are present four weeks or more after the initial phase of infection; may be multisystemic; and may present with a relapsing– remitting pattern and progression or worsening over time, with the possibility of severe and life-threatening events even months or years after infection. Long COVID is not one condition. It represents many potentially overlapping entities, likely with different biological causes and different sets of risk factors and outcomes.” https://www.covid.gov/longcovid/definitions.

Now, as a physician who specializes in the diagnosis of diseases in adults, let me tell you these criteria are not that helpful, especially because the milder symptoms that we see in some patients following COVID can also be reported randomly among the general population. Note that there is no diagnostic test for this condition or host of conditions, unlike blood cell counts for the diagnosis of anemia, blood sugars for the diagnosis of diabetes, etc.

So, the authors of a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection | Neurology | JAMA | JAMA Network) asked the question that all doctors dealing with this condition ask: What symptoms are differentially present in SARS-CoV-2–infected individuals 6 months or more after infection compared with uninfected individuals, and what symptom-based criteria can be used to identify post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) cases?

The investigators analyzed data from 9764 participants in the RECOVER adult cohort, a prospective longitudinal cohort study, and 37 symptoms across multiple pathophysiological domains were identified as present more often in SARS-CoV-2–infected participants at 6 months or more after infection compared with uninfected participants (the occurrence of the symptom had to be 50% higher in the infected group vs. the uninfected group).

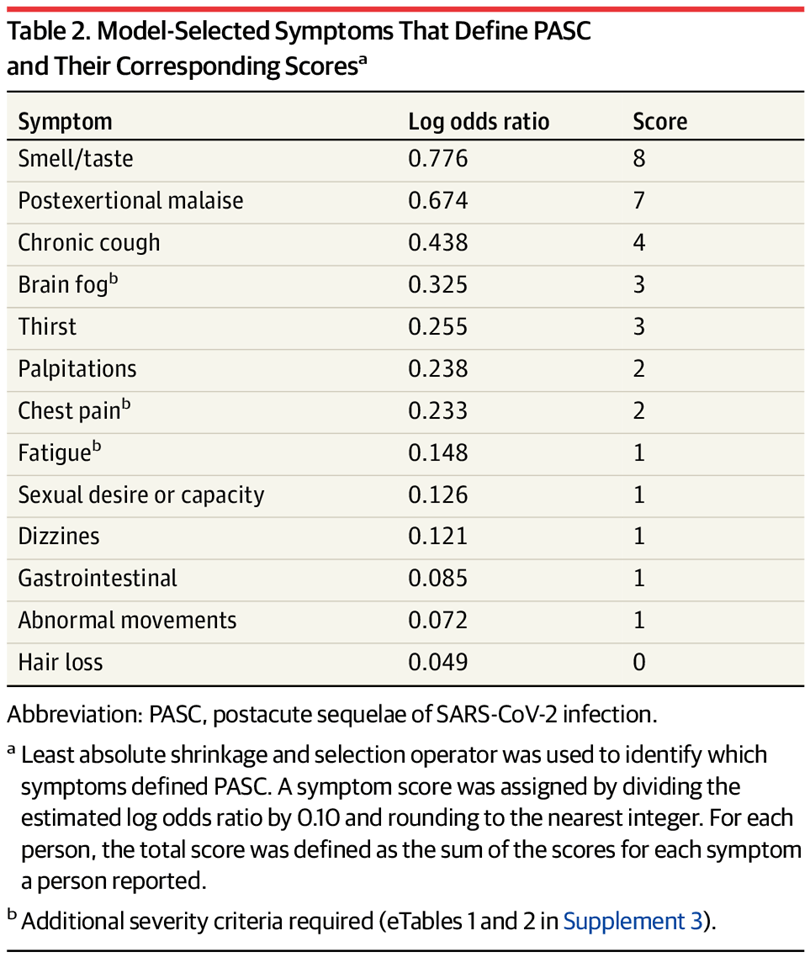

The authors were able to use various methodologies, including statistical modelling, to come up with a list of the most differentiating symptoms and a weighting score for each.

This is in part based upon the actual frequency with which certain symptoms are seen in PASC patients (see Figure B below):

Based upon the symptoms the patient presents with and the scores assigned by the weighting methodology above, we can then see in Figure A above that a score of 12 seems to be the threshold for high confidence in the diagnosis of PASC or Long COVID.

While all of this is nice, and certainly is helpful, I have no doubt that our understanding of this disease (or cluster of related diseases) will change and evolve over time. I also believe that we will develop better diagnostic testing for these conditions. We should all keep in mind that given that there appear to be different subgroups of patients with PASC involving a differing predominance of signs and symptoms (e.g., those that predominantly have postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) or those with a myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome-like presentation) and different underlying potential underlying pathogenetic abnormalities (more on this below), it may very well be that SARS-CoV-2 can produce different pathological sequelae in different people that in turn leads to different manifestations and presenting syndromes. Once we understand these better and can differentiate them into different specific syndromes, the data presented above that reflects the combination of all these syndromes may look very different when we can sort patients by specific syndrome. For example, in the study above, the investigators noted that patients seemed to fall into one of four clusters of symptoms: Cluster 1 was characterized by loss of or change in smell or taste; cluster 2 by post-exertional malaise and fatigue; cluster 3 by brain fog, post-exertional malaise, and fatigue; and cluster 4 by fatigue, post-exertional malaise, dizziness, brain fog, gastrointestinal symptoms, and palpitations.

We also need to be careful to evaluate each patient separately to understand their pre-existing and underlying health conditions as well as their severity of illness with COVID. For example, for those patients who developed severe COVID and required critical care services, we need to be able to distinguish Long COVID or PASC from a well-described post-intensive care syndrome which has occurred in patients long before COVID came on the scene and for which there are many overlapping signs and symptoms.

We still don’t fully understand the difference in risk for Long COVID based upon the variant you get infected with. Earlier studies have suggested that Long COVID was more frequent and more severe when people were infected with variants prior to Omicron (before December 2021). Nevertheless, it is staggering to note that even during Omicron, studies have repeatedly suggested that 10% of those infected will develop Long COVID. There have been inconsistent reports of increased risk for Long COVID if people have more than one infection. However, almost every study shows that being vaccinated significantly reduces, but does not eliminate, your risk of developing Long COVID with breakthrough infections.

Although to some, the percentage of infections resulting in Long COVID may seem small, when applied across large populations, the numbers are staggering. For example, recent estimates are that 65 million people across the globe have Long COVID. I don’t think that the U.S. has begun to appreciate what this will mean to businesses as they will at some point likely experience decreased employee productivity and increases in employee health care and disability costs that may lead to price increases and further loss of competitiveness in the international markets.

An article on May 5 of this year published by Fortune (American worker productivity declines 5 straight quarters | Fortune) revealed that employee productivity is declining at the fastest rate in 75 years, at a time when industrialization, Lean operating methods and automation should be increasing productivity significantly and had, until recently. Of course, economists will have to tease out the effects of disruptions to businesses in 2020, whether remote work has increased or decreased productivity, the so-called new state of “quiet quitting,” and other possible confounding factors, but multiple reports have acknowledged that Long COVID is impacting the workforce, for example, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/one-billion-days-lost-how-covid-19-is-hurting-the-us-workforce, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/01/30/long-covid-has-underappreciated-role-in-labor-gap-study.html, and https://www.fastcompany.com/90777619/long-covid-is-still-draining-many-workers-heres-how-it-affects-productivity, with one study revealing that 22% of those with Long COVID were unable to work and another 45% had to reduce their hours of work https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(22)00491-6/fulltext.

We are still evaluating the underlying pathogenesis of Long COVID following infection with SARS-CoV-2. There is mounting evidence for persistence of either viral proteins or viral RNA in various tissues, months after infection. This could indicate that in some of those with Long COVID, the immune system has been weakened in such a way that the body’s natural protection cannot effectively kill and clear the virus, or that the virus is finding areas of the body in which the cells of the immune system cannot effectively enter and destroy the virus. Persistence of virus can lead to a chronic inflammatory state that may be a factor in the symptoms experienced by those with Long COVID. To explore this hypothesis further, a study is now underway to treat patients with Long COVID with a 15-day course of Paxlovid (this is three times the normal duration of treatment with this antiviral drug that is used to prevent severe outcomes in patients at high risk who are currently infected with SARS-CoV-2) in order to see whether the antiviral can help the body rid itself of the virus and then subsequently relieve the signs and symptoms of Long COVID suffered by these patients.

We have also detected the reactivation of latent viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus and certain herpes viruses with COVID that may play a role in whether someone is at higher risk of developing Long COVID.

Another possibility is that changes can occur due to the inflammation from an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, both at the site of infection, and in distal organs such as the brain. Even a mild SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infection can result in long term changes in the brain.

It also appears that many people with Long COVID have micro-clots (small blood clots that are not normal blood clots, but intertwined with abnormal proteins), and it is suggested that these clots may be interrupting the blood flow in small blood vessels, perhaps decreasing oxygenation of some tissues and organs that might in turn cause some of the signs and symptoms we see in some Long COVID patients.

There is also evidence that SARS-CoV-2 may interfere with an important cellular structure, called mitochondria, that are important for the generation of energy needed for proper cellular function.

A surprising number of people with Long COVID have autoantibodies (antibodies produced by the body against its own cells or cellular components. Autoantibodies, too, can produce a state of hyper-inflammation, which as I noted above may be a contributor to Long COVID signs and symptoms.

It may be that we still haven’t identified the exact causative factor in the development of Long COVID, or it could be that some combination of the factors above contributes to it.

The good news is that there is much research going on in this area, and we are sure to learn more over the next few years. For now, for minimizing your chances of developing Long COVID and some other serious health issues that I will discuss in future blog posts, I give everyone the following advice:

If you have not yet been infected, stay current on the vaccines and try to continue to avoid infection as long as you can.

If you have been infected, stay current on the vaccines and try to avoid a reinfection for as long as you can.

I remain concerned that there is much we still do not know about the long-term health implications of infection with SARS-CoV-2.

A little scary but still I would rather know and plan accordingly. We still plan to travel but for sure our traveling is more guarded with higher quality of masks or more just going via auto where we have much more control of our exposures. I am just very pleased that the research is continuing and that hopefully these horrible viruses will be mitigated with more and more effective solutions. Thanks your Dr Pate for staying touch with studies and translating into laymen terms. [Well not all the terms and wards are understandable. Sorry] Cheers and hope you stay safe. DuWayne

LikeLike

You made me laugh, DuWayne! But, you are right; I need to try to do even better to avoid medical jargon and make these posts more understandable. I will work on that!

Thank you for your comment.

I think you are taking the right approach. Obviously, we need to continue to live our lives, but I simply advocate to those who seek my advice, just add precautions where you can easily do so. Like you stated, continue to travel, but wear high quality masks when feasible. Limit your exposure to large groups of people when possible, especially indoors.

I would also add that we also need to do a bit more pre-planning. I wrote a blog piece on what all that entails last fall before the holidays.

Additionally, we are finally seeing some moves to implement air handling and ventilation enhancements in some public buildings that will definitely make being indoors with groups of people safer. I serve as the chair of the board for the Idaho College of Osteopathic Medicine, and we just held our graduation at the Morrison Center. So, I asked for their air handling and ventilation standards, and they are better than most hospitals! To my knowledge in two years of commencements, not a single case of COVID despite the large numbers of people in attendance. Now, we just need to implement these changes in our schools!

Thanks for your comment, DuWayne, and thanks for following my blog!

LikeLike