Polio and other vaccines have been thrust into the spotlight with a New York Times report on December 13th that was updated on the 15th by reporters Christina Jewett and Sheryl Gay Stolberg revealing that an attorney working with Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. had petitioned the government to revoke (or suspend) the FDA’s approval of the polio vaccine (specifically, the vaccine with tradename IPOL for which the proper name is Poliovirus Vaccine Inactivated) for infants, toddlers and children. The article also indicted that RFK, Jr. has expressed interest in having this attorney serve in the U.S. Health and Human Services Department as general counsel to the organization that President-elect Trump has nominated RFK, Jr. to lead as cabinet secretary.

In the petition, the attorney argues that the basis for the request is that there were not properly controlled and properly powered double-blind clinical trials of sufficient duration to assess the safety of this vaccine.

It should be noted that this polio vaccine is the only polio vaccine licensed for use in the U.S.

Today, the globally available polio vaccines are generally referred to as IPV (inactivated poliovirus vaccine) and OPV (oral poliovirus vaccine). Though people my age will recall getting a “sugar cube” polio vaccine in elementary school, OPV is no longer approved for use in the U.S. (I will explain below), but OPV continues to be used through much of the world due to its lower cost and ease of administration (compared to IPV which is administered by injection).

Jonas Salk invented IPV and it underwent clinical trials beginning in April of 1954. One year later, the results showed that the vaccine was safe and effective, and the vaccine was licensed for use in the U.S. and many countries of the world. The oral polio vaccine was invented by Albert Sabin and licensed in 1961. It was subsequently licensed in 1963 in a trivalent form that would include all three serotypes (strains) of the poliovirus.

What is the poliovirus?

The poliovirus is an RNA virus that belongs to the family of picornaviruses and a specific group of these viruses referred to as enteroviruses, so named because they are transmitted through the gastrointestinal tract. Humans are the only known natural host for this virus, which likely explains the success of elimination efforts through vaccine programs.

As alluded to above, the virus is transmitted through the fecal-oral route (the virus is shed in the stool of those who are infected, which can then contaminate the person’s hands and be transmitted to another person through direct contact, who then ingests the virus and in turn becomes infected) and potentially an oral-oral route (virus can be present in saliva soon before and after the onset of symptoms). Thus, transmission often occurs with young children. Children can also shed virus in their nasal secretions. The period of viral shedding is several days to several weeks.

As mentioned above, there are three serotypes of poliovirus (meaning three distinct types or strains of the virus) that can cause disease in humans (and infection with one serotype is not protective against infection with another), cleverly named serotypes 1, 2 and 3. These also are sometimes referred to as wild type 1, 2, and 3 (meaning the form of the virus that originally occurred in nature). After a global eradication effort with vaccines, serotypes 2 and 3 were certified as globally eradicated in 2015 and 2019, respectively. As for serotype 1, as of 2020, it had been eliminated from every country in the world except Pakistan and Afghanistan.

What is polio?

Polio is generally the term used to refer to the disease caused by infection with the poliovirus. Though the disease can have quite a range of presentations and consequences, many people use “polio” to refer to the most severe form of disease that is technically referred to as poliomyelitis.

The majority of infections with the poliovirus do not produce symptoms or signs of disease (~72% of cases are asymptomatic). However, these children shed virus and can infect others. About 24 percent of infections in children cause mild illness characterized by fever, sore throat, headache, and in some cases, a rash. These symptoms generally resolve within a week.

Nevertheless, the virus replicates (divides to form more virus) in the oropharynx (throat and nose) and in the gastrointestinal tract, and from there moves to the tonsils, lymph nodes, and from there, the bloodstream. In most cases, the body’s immune defenses can contain the virus, but in some individuals, the virus will seed (meaning the virus lands there and hangs out) the spleen, bone marrow, muscle and other deeper and more remote lymph nodes. It is in these individuals that a second, much more significant amount of the virus can enter the bloodstream and, in these cases, the brain and spinal cord can be infected. When this happens, we most often see one of two forms of disease – nonparalytic aseptic meningitis (meaning an inflammation of the lining of the brain and spinal cord with fever, headache, neck stiffness, and back pain; but without paralysis and without virus detectable in the spinal fluid) or paralytic poliomyelitis. The nonparalytic form of disease generally will resolve completely over time.

Paralytic poliomyelitis is the most feared outcome of infection. We cannot predict who will develop this. These children (or sometimes adults) may not have any of the initial symptoms listed above for those with symptomatic infection, or they may have these symptoms and appear to be recovering when within the next days to weeks, they now experience fever, headache, muscle pains, and muscle spasms involving their limbs and back. Within 2 – 4 days, they may develop acute flaccid paralysis (meaning sudden weakness of the arms and legs that are just limp with no muscle tone). Fortunately, in most cases, the paralysis will involve only one side of the body, and more often the legs than the arms, however, in the most severe form, the paralysis can affect all limbs on both sides of the body and even the muscles required for breathing and swallowing (these are the cases frequently seen in “iron lungs” if they survived). [The case fatality rate (CFR) for paralytic polio is 2 – 5% among children and as high as 15 – 30% for adolescents and adults. The CFR for those with the most severe complete paralysis form of disease ranges from 25 – 75%.]

Only about 10 percent of those with paralytic poliomyelitis will experience a complete recovery, though those with one-sided paralysis and persistent weakness can improve over time. However, in a cruel twist of fate, anywhere from 15 – 40 years after seeming recovery or improvement, 25 – 40% of those who contracted paralytic poliomyelitis as a child can experience new onset muscle pain and an exacerbation of existing weakness or even new weakness or paralysis in another form of disease that we refer to as post-polio syndrome.

Prior to the availability of vaccines, polio disabled up to 21,000 people a year in the U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was infected at age 39 and developed paralytic poliomyelitis. He continued to have weakness of both legs and used braces and eventually a wheelchair while in office as President of the U.S. Senator Mitch McConnell was infected at age 2 and developed paralytic poliomyelitis, predominantly affecting his left leg, but fortunately, recovered strength in that leg over time with physical therapy.

Inactivated Polio Vaccine

The clinical trial for the IPV was the largest clinical trial that had ever taken place in U.S. history – including 1.5 million children in 211 counties in 44 states- and far larger than we typically conduct for phase III clinical trials of vaccines today. In this study, 623,972 children received either the vaccine or a placebo (placebo controls), and the remaining more than 1 million children were observed with no intervention (observed controls). The vaccine was 80 – 90 percent effective in preventing paralytic poliomyelitis. Given by injection, the vaccine would not be expected to prevent infection from a virus that infected the gastrointestinal tract through ingestion, but on the other hand, there could be no shedding of virus in a vaccinee’s stool to potentially infect an unvaccinated close contact.

In more recent studies of IPV with our ability to measure neutralizing antibodies, 83 infants had detectable neutralizing antibodies 13 months following a series of three IPV doses of vaccine as follows: 97.6% (type 1), 100% (type 2) and 100% (type 3). For all subjects tested, titers of neutralizing antibodies rose at least 10-fold after 2 doses and at least 100-fold after 3 doses.

No subjects reported serious adverse reactions (one adult did report redness at the injection site). There were no significant local or systemic reactions. In children, fevers did occur following injection in 7% after the first, 12% after the second, and 4% after the third injection (note that most children received their DPT vaccine dose at the same time, and reported similar proportions with fevers after receiving DPT vaccine only.

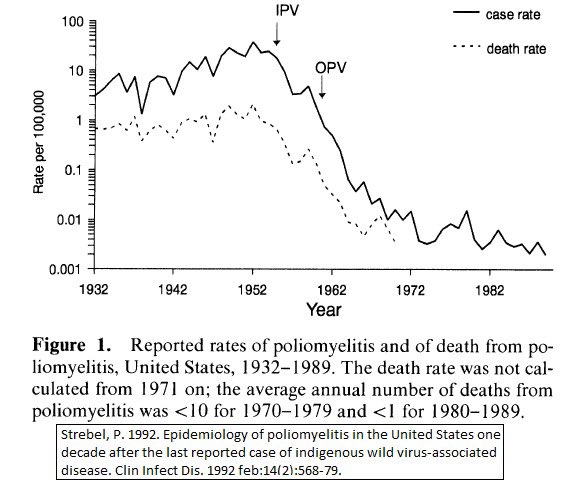

The results were a dramatic decrease in cases of paralytic poliomyelitis following use of this vaccine (and about six to eight years later the use of OPV). The last case of paralytic poliomyelitis in the U.S. from wild type poliovirus was in 1979.

It makes no sense to suspend or end the use of IPV to conduct more studies as requested by RFK, Jr’s attorney. First of all, the vaccine has been in use in the U.S. for 69 years. Almost every living American was immunized with IPV, OPV or both. If the vaccine has safety events even in the range of 1 in 100 million people, we would have seen those safety signals by now. And, of course, there can be no better evidence of vaccine effectiveness when an infectious pathogen has been eliminated from the U.S. following the vaccine campaign. The only cases of polio that we see today are from unvaccinated or immunocompromised individuals being infected with wild type virus from travel to another country, or an unvaccinated or immunocompromised individual being infected by someone from another country travelling to the U.S. and shedding the vaccine derived virus in their stools. Even the most hardened vaccine cynic who is convinced by none of the above would have to admit that the levels of polio disease detected in the U.S. are so low as to make a clinical trial now impossible to assess vaccine effectiveness. Perversely, the only way to retest vaccine efficacy now would be the requested nationwide suspension of use of polio vaccine to allow polio disease to return to levels that would allow for the proposed clinical trial. However, that would lead to a senseless and dramatic rise in polio cases and associated disability, which I cannot imagine would pass the ethical review of any study committee, especially when no reputable virologist, immunologist, physician, or public health official has made a serious argument questioning the safety or efficacy of IPV.

Oral Polio Vaccine

The OPV appears to be similarly effective to IPV, however there are some important differences in these vaccines:

- The OPV is administered by mouth instead of injection.

- The OPV contains weakened strains of poliovirus that are not able to cause neurological disease, but do cause a low-grade infection of the gut, whereas the IPV contains inactivated virus that cannot replicate and cannot cause infection.

- Persons who receive OPV can shed these weakened polioviruses in their stool and can infect unvaccinated close contacts. Because IPV is given as an injection, there is no shedding of the vaccine virus and the vaccinated person poses no risk to others.

- Because the weakened polioviruses are designed to infect the gut in order to create the immune protection, this vaccine should not be given to immunocompromised individuals, whereas IPV is safe in this regard for persons who are immunocompromised. In about 1 in every 2.4 million people who receive OPV, in the process of infecting the gut, the virus can revert to the form that can cause neurological disease and the vaccinated person can develop vaccine-associated paralytic polio.

For all these reasons, the U.S. discontinued the use of OPV in 2000 because polio elimination had been so successful that a person, although extremely rare, would now be more likely to develop paralytic poliomyelitis from the OPV vaccine than from wild-type virus.

However, many countries of the world use OPV for their vaccine responses to polio outbreaks. In Pakistan and Afghanistan, it is very difficult to administer injectable vaccines throughout the country, and at times, the necessary health care professionals needed to administer injections have been targeted. OPV is a less expensive and much easier option to distribute, especially to remote areas of a country. However, for the same reasons as above, if someone receives OPV in another country and then travels to the U.S., they may be shedding the vaccine virus and this would pose a risk to unvaccinated Americans, as unfortunately happened to a young man in New York state who is now paralyzed.