There are four types of influenza viruses – A, B, C and D. Types A and B are responsible for the annual influenza epidemics that occur in humans, and type A viruses are the only influenza viruses known to cause pandemics. The general requirement for an influenza virus to cause a pandemic is for the virus to be sufficiently different from prior circulating viruses such that there is little to no immunity in the population. Influenza C viruses cause such mild illness in humans that we rarely identify those infections and we do not consider influenza C viruses to pose a pandemic threat. Influenza D viruses primarily infect cattle and can spillover to other animals, but pose little threat to humans.

Influenza viruses are RNA viruses and thus are prone to replication errors and the accumulation of mutations. Under normal circumstances, these mutations are incremental and do not result in wholly antigenically distinct viruses (meaning that our immune systems would not recognize them). This is referred to as antigenic drift, and it happens frequently enough that we experience yearly epidemics during the flu season. Antigenic drift involves minor changes in the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins of the circulating influenza A viruses, such that it is necessary for us to update the influenza vaccines every year, however, not so significant of changes that some degree of cross-reactive immunity would not exist or that a new subtype of virus would emerge (the latter developments would represent antigenic shift, as opposed to drift).

Subtypes of influenza A viruses are characterized by their hemagglutinin and neuraminidase protein characteristics. There are 18 known subtypes of hemagglutinin proteins that are represented by the letter H followed by a number (H1 – H18), and 11 known subtypes of neuraminidase proteins that are represented by the letter N followed by a number (N1 – N11). The subtypes of influenza A viruses are then described by the combination of the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase subtypes. The influenza A subtypes that contribute to our seasonally recurring flu seasons are H1N1 or A(H1N1) and H3N2 or A(H3N2).

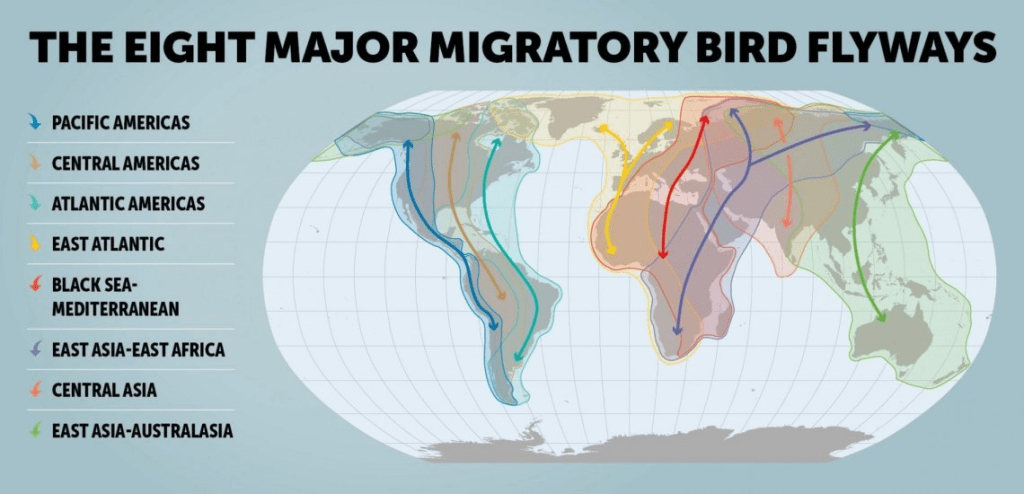

All known influenza A subtypes exist in aquatic birds, which serves as the reservoir for influenza A viruses. These aquatic birds are migratory birds and they can carry and spread the virus along their flyways.

In wild ducks, these viruses replicate in the cells lining their gastrointestinal tracts, but do not make the ducks sick. The ducks excrete very high levels of the virus and can contaminate fresh water ponds, lakes and rivers, as well as land that they fly over or dwell on, which in turn often leads to infections of domestic birds and poultry. Large numbers of baby ducks are hatched each year, and they can be infected by virus in the water, and further contribute to the spread of the virus.

It is believed that all mammalian influenza viruses derive from the aquatic bird (avian) influenza reservoir, and phylogenetic analyses (the study of the evolution of genetic sequences) suggests that both swine and human influenza A viruses evolved from avian influenza viruses.

Besides accumulating mutations as a result of errors in transcription (the process of copying the virus’ genetic material during virus replication in order to make copies of the virus’ proteins, which in turn can be assembled into new virus progeny), influenza viruses can undergo the process of reassortment.

The diagram above shows one such example that lead to the H7N9 virus that infected humans in China back in 2013.

The influenza virus has eight genes coding for eight influenza A proteins (PA, PB1, PB2, nucleoprotein, hemagglutinin, neuraminidase, nuclear export protein and membrane protein. If a host is infected with two or more different influenza viruses, these viruses can exchange genes resulting in a new virus that has genes from more than one influenza virus. In the above example, the H7N9 virus got its hemagglutinin protein H7 from a domestic duck and its neuraminidase protein N9 from wild birds, while the other genes came from multiple H9N2 viruses in domestic poultry. The significance of this is that the new resulting virus can have much more antigenic variation from that of previously circulating influenza viruses (antigenic shift) and the new collection of proteins may confer biological changes to the virus that might result in enhanced transmission to humans, and even more concerningly, the capability for enhanced forward transmission (human-to-human spread).

The first human influenza virus was isolated in 1933. The largest influenza pandemic in just over 100 years was the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 – 1919. That was an H1N1 virus, and there is evidence to suggest that it was an intact avian influenza virus (not the result of reassortment) that appeared in humans or swine before 1918 and then replaced the previously circulating strains when it caused the pandemic.

The Asian influenza virus (H2N2) replaced the 1918 H1N1 virus in 1957 when it caused a pandemic. The Hong Kong influenza virus (H3N2) appeared in 1968 when it sparked a pandemic, and then the H1N1 virus reappeared in 1977.

Sources

Influenza: An Emerging Disease. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2640312/.