In my last update, I expressed concern that something has changed (for the worse) with this virus. We were seeing a change in virulence to cattle in California with prior reports of case fatality rates in infected dairy cattle being 1 – 2%, but in California herds, the case fatality rates were being reported in the press as 10 – 15%. Further, while we were told that prior to the identification of the California outbreaks, symptomatically ill cattle seemed to be recovering within about a week, we were now seeing evidence in California herds that it was taking several weeks for recovery of those that survived.

In the latest update from the CDC, H5 Bird Flu: Current Situation | Bird Flu | CDC, it states:

While the current public health risk is low, CDC is watching the situation carefully and working with states to monitor people with animal exposures.

CDC is using its flu surveillance systems to monitor for H5 bird flu activity in people.

Both the USDA and the CDC have commented as to how the H5N1 virus is spreading. The USDA provides:

HPAI (HPAI stands for highly pathogenic avian influenza) is a very contagious and often deadly respiratory disease of poultry, such as chickens, turkeys, and geese. It is often spread by wild birds and can make other animals sick, too. It’s a major threat to the poultry industry, animal health, trade, and the economy worldwide. Caused by influenza type A viruses, the disease varies in severity depending on the strain and species affected.

HPAI H5N1 (this is now a reference to the specific avian virus that is spreading in dairy cattle in the US) viral infection was first confirmed on a dairy premises on March 25, 2024. USDA, in coordination with States, took immediate action to conduct additional testing for HPAI, as well as viral genome sequencing, to learn more about the virus and how it was spreading among dairy cattle. USDA and State teams conducted extensive epidemiological work to investigate the links between HPAI-affected dairy premises and evidence of spillover into poultry premises.

Continued disease transmission regionally within the country is due to several factors. In addition to the movement of livestock, transmission between farms is likely related to normal business operations such as numerous people, vehicles, and other farm equipment frequently moving on and off an affected premises and on to other premises. Importantly, it is not currently believed that the disease is spread onto dairy or poultry premises by migratory waterfowl—this is supported by both genomic and epidemiological data analysis.

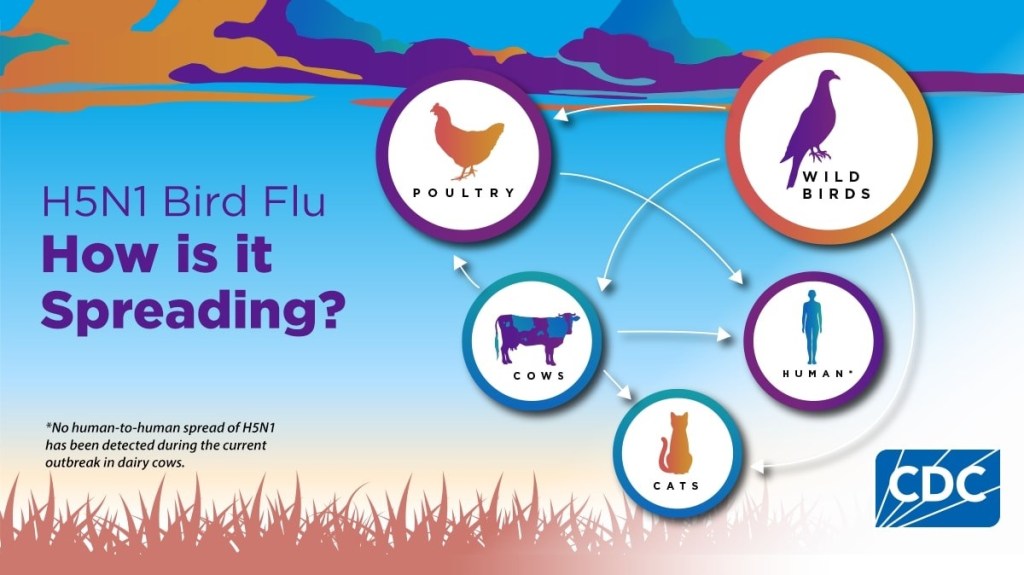

The CDC provides the following graphic to describe routes of transmission to various species:

But, as you can see for yourself, this leaves many questions unanswered, as to how the virus is spreading within herds and how people are infected by cattle. Further, while both agencies emphasize that no human-to-human spread of H5N1 has been detected (a true statement), many of us feel that the CDC has not done enough testing to assure us this is the case.

There is one troubling case of note. A patient in Missouri in August of this year with a chronic respiratory illness was admitted to the hospital with gastrointestinal symptoms. Testing was positive for influenza A and the CDC confirmed that the patient had H5N1. The patient had no history of exposure to infected humans or animals and we are told that the patient had not ingested raw (unpasteurized) milk. The epidemiological investigation revealed that seven persons (1 family member and 6 health care workers) had symptoms that warranted investigation given their exposure to this patient. Five of the six health care workers were tested by serology (testing for antibodies to the H5N1 virus that would provide evidence of prior infection) and all tested negative, suggesting that their symptoms were due to something other than infection with the H5N1 virus. Several different tests were conducted on the index patient (the patient who was hospitalized and first identified as having H5N1 infection) and the household contact. Testing results of the sera from the index case and their household contact were similar: both showed evidence of an antibody immune response to H5 in only one assay (that detects H5 neutralizing antibodies), but not on the other serologic assays used to detect infection. The CDC interprets the results as follows:

The weak immune signal suggests that it is possible that both of these people may have been exposed to H5 bird flu despite the fact that they did not meet accepted thresholds for seropositivity. These similar immunologic results coupled with the epidemiologic data that these two individuals had identical symptom onset dates support a single common exposure to bird flu rather than person-to-person spread within the household. Intensive epidemiologic investigation has not identified an exposure to an animal or animal product exposure to explain these possible infections, and these serologic data cannot further elucidate the exposure leading to these possible infections.

While I personally think that there likely is little or no human-to-human spread, neither agency has advised us of the plan to ensure that remains the case, particularly as we prepare to enter the human influenza season with the risk of transmission of human influenza viruses to cattle and the risk for reassortments that might result in an avian influenza virus with more efficient transmission to and between humans. Further the failure to contain the spread of the virus among cattle after 7 months is not reassuring most of us that the response to this event is as vigorous as it needs to be. Poultry outbreaks have been identified in 48 states, and 14 states have outbreaks among dairy herds.

Finally, the CDC is reporting 36 human infections thus far this year, but my concern is that more than half of these were just detected in the past 2 – 3 weeks coincident with the changes that we have noted in the virus virulence among cattle. Further, many of us following this matter closely strongly suspect that many infections have gone undetected and that there still is not adequate testing being done. We do know that there are more cases awaiting confirmation that will likely be added to this tally of human infections. The Seattle Times reported on Friday that

the number of workers at a Franklin County commercial egg farm who have now tested positive for bird flu has increased to eight, according to preliminary test results.

These are the first known human cases of H5N1 in the state of Washington. If these are confirmed, this will bring the total of human infections to 23 just from this month. Fortunately, all cases thus far have been considered to be “mild.”

KFF Health News on Friday reporters cannot determine why we are seeing this spike in cases, because surveillance in humans “has been patchy for seven months.”

KFF Health News obtained hundreds of emails from state and local health departments through an open records request. They report:

Despite health officials’ arduous efforts to track human infections, surveillance is marred by delays, inconsistencies, and blind spots.

Several documents reflect a breakdown in communication with a subset of farm owners who don’t want themselves or their employees monitored for signs of bird flu.

Other emails hint that cases on dairy farms were missed.

Researchers worldwide are increasingly concerned.

“I have been distressed and depressed by the lack of epidemiologic data and the lack of surveillance,” said Nicole Lurie, formerly the assistant secretary for preparedness and response in the Obama administration.

Maria Van Kerkhove, head of the emerging diseases unit at the World Health Organization, said, “We need to see more systemic, strategic testing of humans.”

Contributing to the problem are (1) the fact that the USDA cannot force dairies or poultry farms to cooperate, (2) it has been reported that some veterinarians have been threatened by some farmers with loss of their employment if they report the illnesses, (3) many of the workers have no health insurance and/or lack the ability to take time off to see a doctor without loss of pay and possibly even their jobs, and (4) the CDC cannot come in to investigate unless invited by the involved state. Additionally, many local health departments are underfunded and understaffed to be able to conduct the investigations thoroughly.

Personally, I fear that there is also a sense of complacency given that no human-to-human transmission has been documented thus far and that the illnesses have so far been mild. But, if we allow this spread to continue, that could change over night.

A newly published article indicates that the H5N1 influenza virus obtained from an infected worker was capable of being transmitted through respiratory droplets in a high-containment laboratory environment to mice and ferrets (influenza infections in ferrets more closely resemble human influenza infections than those in mice), and that the infection in the ferrets that were directly inoculated with the virus was 100% lethal, in contrast to studies with prior bovine H5N1 virus, which caused severe disease in ferrets, but limited mortality. Further, the investigators determined that the virus may be capable of binding to and replicating in human respiratory tract cells. The isolated virus has the mutation PB2-E627K, known to increase the efficiency of transmission of avian influenza viruses in mammalian species. This study suggests that we need to carefully monitor this situation, be careful before concluding that there is no respiratory droplet transmission, and be alert for the potential of this virus to cause severe disease in humans.

Finally, many of us remain concerned that there simply is not enough transparency by both the USDA and the CDC.

I do not know whether H5N1 will eventually spark a new pandemic, but I know that if you were watching a pandemic unfold before our very eyes, which we almost never do, this is the progression of evolution that you might expect to see.