Surveillance and Containment of Novel Infectious Agents with Pandemic Potential – We are Not Good at This

The old saying, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” is no more apt than in the field of global outbreaks and pandemics. In other words, the cost of responding aggressively to novel infectious agents with pandemic potential, even if they ultimately do not cause an epidemic or pandemic is far less costly (in terms of dollars, societal costs and health care costs) than if we respond lethargically and allow the infection to spread among animals and eventually to humans and beyond the initial geographic borders before we decide to get serious about it. We need only look the past two years at our non-response to Mpox outbreaks in Africa over decades that ultimately became a Public Health Emergency of International Concern with global spread in 2022. You would think “well, surely we learned our lesson from that,” but now two years later, we are faced with a second Public Health Emergency of International Concern with another outbreak in Africa with yet a different strain of Mpox that is now showing up in countries that have never had cases of Mpox before and appears to potentially cause higher morbidity and mortality, and unlike the strain involved in 2022 that appeared to be largely spreading among communities of men who have sex with men, this one appears to infect a much broader range, including children and heterosexual adults.

In addition to early interventions being cost-effective and potentially sparing many lives, just undergoing a systematic epidemiological investigation, as well as studies of the infectious agent and its biological properties, receptor affinities, mode of transmission, and pathogenesis (the mechanisms by which it produces disease) as well as studies of the immune response of those who are infected and potential vaccines or therapies, would generate tremendously valuable information about the specific infectious agent, but also potentially add to our knowledge about related infectious agents (e.g., our studies and knowledge of smallpox have accelerated our knowledge and vaccine options against monkeypox) and contribute to our general understanding of bacteria, viruses, fungi, prions, or whatever the infectious threat turns out to be.

Now, for at least the third time, in just two years, we appear to be making all the same mistakes and omissions again as we are faced with a new strain of avian influenza virus that is spreading largely uncontrolled among U.S. dairy farms.

In late 2000, when my soon-to-be coauthor contacted me about the idea of writing a book, after my wife had already planted that idea in my head six months earlier, I became convinced that there was a need for us to write that book (Preparing for the Next Global Outbreak: Lessons from the Schoolhouse to the White House), because it was already becoming clear to me that we were making many mistakes and appeared not to be learning from these. That book was the opportunity for us to chronicle our learnings from the COVID-19 pandemic and to capture the learnings, as well as laying out 117 specific recommendations with the hopes that the next time we were threatened with a global outbreak, hopefully it would be unnecessary to repeat all these mistakes.

An article was published in Nature two days ago in which some influenza experts offered a review and their perspective on the global H5N1 (this is the scientific reference to a particular avian influenza [bird flu] virus) influenza panzootic (this is the term for a pandemic in animals) in mammals The global H5N1 influenza panzootic in mammals | Nature. I think this will be of interest to readers on my blog, so I will summarize it below:

In their introduction, they call out a point that I have made a number of times on the radio show I appear on weekly (Idaho Matters with Gemma Gaudette, Boise State Public Radio https://www.npr.org/podcasts/605235114/idaho-matters): Influenza A (this group includes some human seasonal influenza viruses, as well as avian influenza viruses) has been responsible for more pandemics among humans than any other organism in history to our knowledge, but definitely in the past century. Thus, any outbreak of influenza A among humans or animals deserves our attention, at the very least.

While generally we think of avian influenza viruses as causing infections in waterfowl and wild birds that then contaminate feed or feeding grounds and infect domestic birds, especially poultry, the current global outbreak is different and concerning due to: (1) the rapid global spread of the virus including to South America and Antarctica for the first time; (2) the rapid evolution and changes to the virus resulting from reassortment (this is a process characteristic of influenza viruses whose genetic material largely consists of 8 segments, of which one or more can be easily swapped with another influenza virus when a human or other animal is infected with, for example, one avian influenza virus and one human influenza virus, resulting in a significant change in the virus that can lead to adaptation of the avian virus to better infect mammals, which otherwise the avian influenza virus is quite limited in its ability to do), and (3) the frequent spillover to land and marine mammals, many of which we have never detected H5N1 infections in before.

For the first time in the decades that we have been aware of the virus, the H5N1 virus has demonstrated sustained mammal-to-mammal transmission among very diverse species, including most recently (first detected in March of this year) outbreaks among dairy cattle farms in a growing number of herds in a growing number of states in the U.S.

All of these factors should be increasing our assessment of risk for spillover to humans (and we have now detected 15 such cases in the U.S., with concern that there could be many more undetected cases) and the potential (even though currently thought to be low) for this virus to develop the potential to cause a human pandemic.

In the past, with one notable exception (see below) avian influenza viruses have caused human pandemics, but only after first infecting swine that served as the “mixing bowl” for reassortment of the avian influenza virus with other influenza A viruses that gave the avian influenza virus the ability to efficiently infect humans and the ability for efficient human-to-human transmission. These authors lay out information that we have learned that raises the potential that the currently uncontrolled spread of the virus in other mammals, particularly dairy cows, may serve the “mixing bowl” function that swine have done in the past.

The authors include the graphic below to demonstrate how the H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza A virus has spread from being isolated to Asia to encompassing the United States within 15 years, and several years later, throughout much of the world.

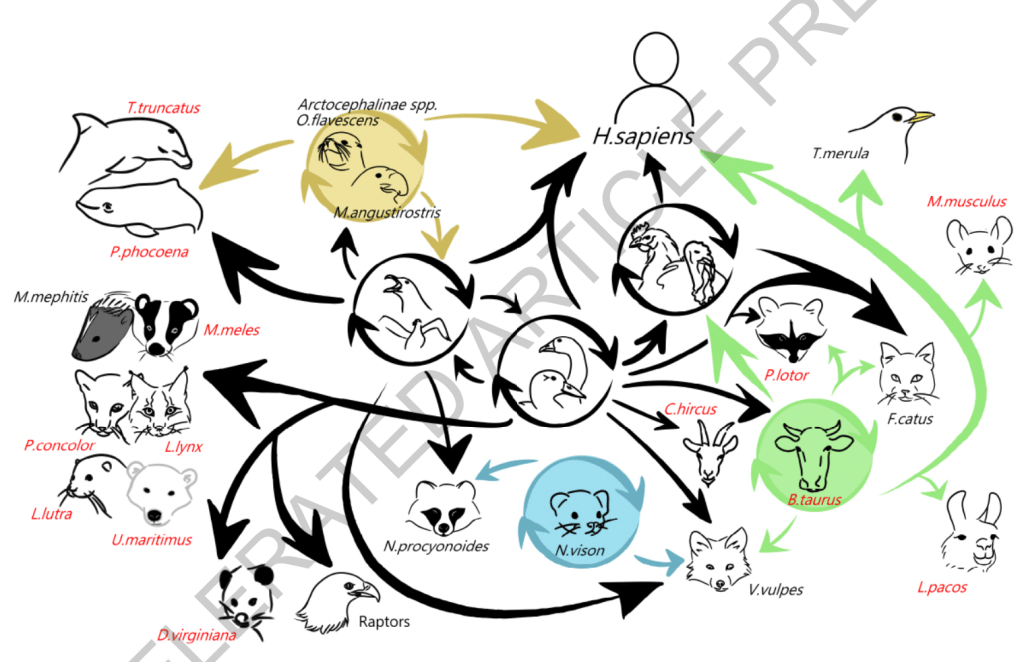

This next graphic depicts the range of mammalian species that have been infected by the virus, most of these for the first time in the virus’ history to our knowledge:

We need to keep in mind that spread of the virus to and among a greater number of mammals presents the virus with many more opportunities to evolve in ways that increase transmissibility and that equip the virus with more defenses against mammalian immune responses. Both of these, in turn, increase the threat of more efficient spread to humans, and ultimately could result in more efficient transmission among humans, the final step between this remaining a panzoonotic event and becoming a human pandemic.

The authors point out that the change in threat level occurred in 2020 when a new genotype (genetic form of the virus) developed that is referred to as clade 2.3.4.4b (you can think of clade as another word for strain). That lead to greater spread around the world and greater spread to a wider range of animals.

In the past, when a different avian influenza virus spread to the U.S. from Asia, outbreaks were contained with surveillance and culling of infected poultry. This time is different. Culling of infected poultry has not stopped the spread of this virus and now, for the first time, outbreaks are occurring on an increasing number of dairy farms in a growing number of states. It appears that wild migratory birds are continuing to introduce the virus on dairy and poultry farms as they fly over, including during migration.

The current clade spreading among dairy cattle in the U.S. is the clade 2.3.4.4b – the result of the virus having undergone a number of reassortments (swapping of segments of the genetic material with other influenza viruses the host was infected with) – going back to a reassortment between an H5N8 avian influenza virus and a Eurasian low pathogenic avian influenza virus.

Initially, there was a single spillover event of the H5N1 virus from wild birds to U.S. dairy cattle (in Texas), likely in late 2023 or early 2024, after which there was onward transmission from cattle to other cattle likely through virus on milking machines, though the contribution of respiratory transmission remains unclear. There was subsequent spread to other dairy farms by transport of infected cattle, as well as spillover events from cattle to other animals and wildlife, most notably cats that drank raw milk spillage on these farms.

The authors then pose and try to answer the critical question: Could this virus spark a pandemic?

The authors point out that for an influenza virus to spark a pandemic, it must fulfill two key criteria. First, the main attachment protein of the virus (i.e., hemagglutinin, from which each virus is given the “H” designation – in this case, H5) must be antigenically novel (meaning that the immune systems of a sufficiently large portion of the population have not previously been exposed to it and would not be able to recall prior immune memory to make a rapid antibody response). This criterion is fulfilled, as human seasonal influenza viruses are of the H1 or H3 type, predominantly. H5 has never before circulated in humans, and thus, it would be antigenically novel, and further, there is no evidence to support that humans would have cross reactive immunity from any of our past hemagglutinin protein exposures.

The second criterion is a much higher, but not impossible, bar to meet: efficient transmission between humans.

Based on our current understanding, we believe that would require three changes to an avian influenza virus (and these would most likely occur through the reassortment process). The first change is in the viral polymerase (PB2, PB1, and PA proteins) that helps the virus exploit mammalian host machinery to replicate (make the viral proteins necessary to assemble new virions) by way of enabling the avian viral protein able to work with and direct the human cellular components it needs for the process of protein synthesis. A second change must occur in the hemagglutinin protein (remember, this gives the influenza virus its H designation) to help the virus bind strongly to cell surface receptors abundant in the human upper respiratory tract (URT) since avian influenza viruses preferentially use cell receptors with α 2, 3 -sialic acids attached to their cell surface glycoproteins, whereas humans do not generally have this configuration in the upper respiratory tract (rather, we have α 2, 6 -sialic acids on our cell surface glycoproteins). This is critical because levels of virus are highest in respiratory secretions and aerosols when the virus is present in the upper respiratory tract of the person emitting the secretions and aerosols. The third change must stabilize the hemagglutinin protein to tolerate lower pH (a more acidic environment) to prevent destruction of the virus when transiting between hosts through the air. For H5N1 viruses, the highest hurdle appears to be the second criterion. The virus’ polymerase is more prone to adaptation than is the ability for the virus to change receptor affinities.

In 1957, this trifecta occurred during dual infection of an individual animal — probably a human, but possibly another species, such as a pig — with an avian H2N2 influenza virus and a human H1N1 influenza virus that resulted in the emergence of a new influenza virus containing the hemagglutinin, the neuraminidase, and the gene for one of the polymerase proteins (PB1) from the avian virus, along with the remaining five genetic segments from the human H1N1 influenza virus, and it sparked a pandemic.

The remnants of that reassortment H2N2 pandemic virus circulated in humans until 1968, when it was replaced by another reassortment virus, the H3N2 Hong Kong virus — created by the replacement of the hemagglutinin (H2) and polymerase (PB1) genes of the H2N2 virus with two new avian genes, H3 and a new PB1 that triggered another pandemic. The Origins of Pandemic Influenza — Lessons from the 1918 Virus | New England Journal of Medicine (nejm.org)

However, while much less common, and perhaps only a once-in-a-century or longer event, we should keep in mind that the most deadly pandemic (in terms of American deaths on a per capita basis) since the late twentieth century was the influenza pandemic of 1917 -1918 (the COVID-19 pandemic killed a greater number of Americans, however, in 1917-1918, the U.S. population was roughly a third of what it is now, so on a per capita basis, the U.S. mortality rate was higher for the influenza pandemic) was caused by an H1N1 virus for which there is no evidence of reassortment, meaning that this avian virus most likely infected humans and then evolved within humans to acquire these necessary mutations and enhanced transmission.

I am concerned that we have uncontrolled spread of the H5N1 virus among dairy cattle. As we approach our seasonal influenza season, will those working on dairy farms transmit our seasonal virus to these animals, where we know that coinfection can occur in cow utters, and will this potentially serve as the “mixing bowl” to allow mutations and reassortments necessary for the three criteria above to be met?

But while this is a concern yet to materialize, there is already a concerning development that further demonstrates how bad we are at surveillance and containment of novel infectious agents with pandemic potential beyond the fact that thus far, six months later, we still are unable to prevent further spread of H5N1 to more dairy farms in more states (the latest being California). This development gives rise to concern that perhaps the second criterion is becoming closer to being met, while public health and agriculture agencies have largely been mounting a response without any sense of urgency, and in some respects, without any sense.

Here is what happened. An individual in Missouri, with a number of underlying health problems, was hospitalized on August 22 of this year. On September 6, the CDC announced that this person was confirmed to have an avian influenza (H5 – reportedly the sample was inadequate to allow for identification of the neuraminidase “N” component) that was detected through the state’s seasonal flu surveillance system. The patient was treated with antiviral therapy and was able to be discharged from the hospital and has since recovered. This was the 14th case of H5 infection in a human in the U.S. in 2024 (15th case in total – there was a case in Colorado in 2022 in a worker involved in culling infected poultry birds). What was particularly concerning about this case was that the person, unlike all the other reported cases, had no occupational exposure to poultry or dairy cows. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/s0906-birdflu-case-missouri.html.

The significance of lack of exposure history is the concern for whether the patient was infected through community spread of infection – a clear concern that the second criterion that we discussed above may have been met unbeknownst to us. At that point in time, I was hoping that the patient had ingested raw milk, and it seemed an obvious oversight that the CDC didn’t state whether the patient did so in the announcement. It was not until later that the CDC would confirm that the patient had not ingested raw (unpasteurized) dairy products.

Since then, information has been slow to be updated and has dripped in in an ever-increasingly concerning manner, despite the reassurances from public health agencies that the risk to the public remains low. One week later it was disclosed that a “close contact” was also sick at around the same time as this patient. That person was not tested for influenza. In perplexing statements, the CDC stated that it did not believe that there had been spread of H5N1 between the infected patient and any close contact, without offering any basis for that somewhat surprising statement. “There is no epidemiological evidence at this time to support person-to-person transmission of H5N1 though public health authorities continue to explore how the H5N1-positive individual in Missouri contracted the virus.”

Let me explain why this feels like gas-lighting to those of us not privy to all the information that the CDC has about this case, and can only go on the basis of the drips of information made public. So first let me acknowledge that the investigation is disjointed in that the state has original jurisdiction and the CDC can only insert itself to the extent it is invited by the state. Further, I acknowledge that if we had all the information that the state investigators and CDC have, perhaps I would come to the same conclusion that they have. But, with the limited amount of information that has been made public, the CDC’s statements make no sense. First of all, they state that “there is no epidemiological evidence” to support person-to-person transmission. Well, one key tool of an epidemiological investigation is to do contact tracing. They state that a “close contact” was also sick around the same time as the patient, but was not tested for influenza. So, that is concerning evidence. It is not proof, by any means, but we are being told that someone who was in close contact with the patient was also sick, but we don’t know what illness they had because they were not tested and we don’t know the nature of the close contact. That raises four possibilities: (1) Close contact infected patient; (2) patient infected close contact: (3) patient and close contact were infected by a common unidentified source; or (4) patient had avian influenza infection, but close contact has a contemporaneous, but different and unrelated illness. Despite having no answers, these are not unanswerable questions. The fourth possibility is the most important to answer, and the way you answer that in someone who is no longer sick and therefore cannot be tested with our influenza tests that we use on sick patients is to do a serological test, i.e., we check the person for antibodies to H5N1 in their blood. In response to questioning about this, we are told that the public health authorities were contemplating such testing. (You have to read this next sentence as if I am yelling it, because I was in my head). Contemplating it, good heavens, it takes me 5 minutes to contemplate that kind of testing in my medical practice! All you need is a tourniquet, gloves, a specimen tube, an alcohol swab, a needle and syringe or vacuum device and a band aid. We all have had blood drawn like this and it is no big deal except for those of us with aversions to needles. This simple test would answer the most important question. If the contact (which was later disclosed to be a household contact, which makes this even more likely to be related infections) is negative for antibodies, then great; we can let this go. But, if positive, then we need to explore the timing of onset of their respective symptoms and a detailed review of their activities and contacts during the days leading up to their infections to better understand did one infect the other or did they most likely have a common source exposure.

Another week later the CDC informs us that no source has been identified for the patient’s avian influenza infection (this means that this case is distinctly different than all the other known cases, and remains concerning for community spread because there has been adequate time for the epidemiological investigation to be completed). Now we are told that there were two health care workers who were exposed to the index case (the hospitalized patient) who subsequently developed respiratory symptoms after caring for the patient before respiratory precautions were put in place. One tested negative for influenza during the illness, serology testing was pending for the second case.

Then, we get a bombshell update on September 27 from the CDC. An additional four (i.e., now total of 6) health care workers developed respiratory symptoms following the identification of the index case (hospitalized patient), and 3 of the 4 (5 of the 6) were exposed to the index patient. However, unlike the initial two health care workers who were exposed prior to the institution of respiratory precautions (droplet), the subsequent three had exposures after those precautions were instituted. Drawing some inferences from the statement, it appears that serological tests (antibody testing) is pending for five of these health care workers (apparently, serology is not being performed on the first health care worker who is the only one who had PCR testing for influenza [that individual tested negative]). Frustratingly, the serology testing for the household contact of the index case is still pending.

We are also told that a total of 94 people were exposed to the patient while hospitalized.

So, why am I frustrated and why are so many experts troubled by this situation?

- The fact that the CDC must be invited in to an outbreak investigation by the individual state is reminiscent of the frustration the world experienced as the WHO was unable to investigate the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in China until it was invited in.

- Similarly, the CDC and USDA have limited ability to surveil and manage the H5N1 outbreak on U.S. dairy cattle farms, which has resulted in undertesting, delays in identifying cases, a lack of ability to determine the full extent of the outbreak, and a failure of containing the outbreak.

- The fact that we are still waiting on serological testing results from the household close contact of the index case at 3 weeks now indicates the bottleneck in testing (apparently this testing can only be done at the CDC lab reminiscent of the bottleneck in testing and marked delays in obtaining results that we experienced at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, which blinded us to the extent of community spread of the disease at the time). It also suggests inefficiency of testing. I can generally get serology tests back in 48hours to a week. If there is a reason that this testing takes weeks to perform, then again, the CDC should just tell us. Otherwise, it feels as though they have the results and are not disclosing them, or they are slow-walking the testing.

- The fact that it has taken so long to identify health care workers exposed to the index case and those who experienced symptoms suggests a lack of a sense of urgency in the investigation.

- We are now told that the serological testing of the newly identified symptomatic health care workers will be delayed due to the weather conditions created by hurricane Helene. This is another problem with having only one laboratory (in Atlanta) that can perform this testing. I do not mean to imply that serologic testing is simple, however, it is done many times a day in thousands of laboratories across the country. If there is a reason that this testing can only be performed at the CDC in Atlanta, then just explain that to us. Otherwise, there are many laboratories across the country certified to conduct complex testing, and an effort should be made to speed up this testing and increase its availability now that we have a case that should be considered evidence of community spread, until proven otherwise. (We assume community spread when we cannot identify a source of the infection).

- Recall, that at the time of this patient’s hospitalization August 22, we were at very high levels of COVID-19 across the country. In fact, it would not be surprising that some of these symptomatic health care workers had COVID and not bird flu. However, this is emblematic of the unexplainable, and I think, indefensible, abandonment of infection control practices in hospitals.

Let’s go a little deeper. So, we are told 94 health care workers were exposed to the patient. That means the patient was exposed to 94 health care workers when COVID levels were extremely high.

We are also told that initially no respiratory precautions were in place upon the patient’s admission. We aren’t told what the patient’s presenting signs and symptoms were (something that frustrates many of us that are trying to learn from these cases), but we are told that the avian influenza infection was picked up through the state’s seasonal flu surveillance system. So far, I have not been able to locate the exact criteria used for selection of patients to screen for influenza under Missouri’s surveillance system, but it would make sense that specimens would be obtained from patients with influenza-like illnesses (acute respiratory illnesses, fever, cough, etc.). It can certainly be difficult to distinguish influenza, COVID-19, RSV and a number of other respiratory infections early on in the course of hospitalization. Assuming this to be the case, and I fear that this hospital is no different from most across the country, patients with potentially contagious respiratory infections are being admitted without respiratory precautions, repeatedly exposing staff. And, of course, this also means that patients who already are vulnerable due to the illness they are hospitalized with are exposed to staff and to patients with respiratory infections for whom no respiratory precautions are in place.

Further, note of the 6 health care workers that so far were identified as developing respiratory symptoms after exposure to the patient, only one was tested while ill. That means that we don’t even know the extent that infections are being passed around in hospitals from patients to other patients or health care workers, or vice versa. We also aren’t provided with any information from the CDC’s update as to whether any of these symptomatic health care workers continued to work while they were symptomatically ill (spread to other patients or staff who were now contacts of the health care worker, but not the index patient?), and if they did, whether they were required to wear a respirator mask (I might fall out of my chair if the answer is yes).

- It’s not like this is just all academic. If there is human-to-human transmission of this avian influenza, this is critical to know. It should inform farm and hospital infection control practices and how we handle infections. If there are sustained chains of transmission, then this is of paramount importance, because this means there is a pandemic threat and this calls for an active public health response and an updated pandemic response plan.

The CDC tells us that the public threat remains low. That is very possibly the case. However, that is an assessment based on very sparse and insufficient data. If the seven symptomatic close contacts are all negative on their serology testing, I would totally agree. If the seven symptomatic close contacts are all positive on their serology, then we have either got a highly infectious disease with an effective reproduction number of near 7 (the index case infected 7 people; for a pandemic to occur, one only needs this number to be greater than 1 if the other criteria we discussed above are met) or there is far greater community spread (i.e., not all of these people were infected by the index case, therefore there are many other undetected sources of infection out there) that we don’t know about. If it is the latter, and we simply have 6 out of 94 health care workers previously infected by someone other than the index patient (and we are not told that any of the remaining 88 health care workers are being tested in the event they had asymptomatic infections, or were pauci-symptomatic and their symptoms were so mild that when questioned weeks later they forgot about them), then we have already lost control of this.

For now, we will just wait for the drips of continued updates and try to piece this altogether as we get additional information that we should already have by now.

Thank you!

LikeLike