Part III (continued)

Has SARS-CoV-2 become a seasonal virus and has COVID-19 become a seasonal disease?

In my last blog piece (Part III) in this blog series entitled: “A Comprehensive Update on SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19,” we began addressing whether the evidence supported some claims, explicit or implicit, that SARS-CoV-2 is now a seasonal virus. We discussed what it means to be a seasonal virus, what the epi curves look like for classical seasonal viruses (both in the northern and southern hemispheres), what the epi curve looks like for SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 (quite different), and what factors can contribute to the seasonality of some viruses.

Having established that SARS-CoV-2 is not a seasonal virus, in this blog post, though we still have many unanswered questions as to how and why the cases of COVID-19 tend to come in waves or surges as depicted in the epi curve for SARS-CoV-2 infections, we will explore what we do know and what the current thinking is related to these recurring surges throughout the year. I will introduce readers to the concepts of viral fitness, immune evasion and the evolution of variants as it appears that waves or surges likely have more to do with human behavior (when we tend to be together indoors with large numbers of people for long periods of time) and the everchanging immune landscape of the population as prior immunity from infection or vaccines wanes and as new variants develop new mutations that reduce the effectiveness of our existing antibodies against them.

We’ll start with a study that came out just a week ago[i]. As most people who follow me on X or on the weekly radio show (Boise State Public Radio with host Gemma Gaudette) know, I follow new surges across the world, as they often give me forewarning as to surges that will soon follow in the U.S. However, it did intrigue me as to those surges that occurred in other parts of the world that never materialized in the U.S. Why not? And, even surges that occurred in the U.S. did not always impact all of the continental states. Why not? So, this study is interesting in that it looks at the peaks of COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations that occurred in the Bronx, New York and compares them to those peaks that occurred nationally. In an attempt to understand these differences, the authors conducted a comprehensive analysis of the genomic epidemiology of the four dominant strains of SARS-CoV-2 (Alpha, Iota, Delta and Omicron) responsible for COVID-19 cases in the Bronx between March 2020 and January 2023.

Most of us will remember that New York City (the Bronx is a borough of the city) was the epicenter of the pandemic in early 2020 with hospitalizations for COVID-19 overwhelming hospitals resulting in the need for mobile and remote treatment centers to be set up, including use of a convention center, and volunteer health care professionals to travel from all around the country to help take care of all these patients. Being so early in the pandemic, with no preexisting immunity and no specialized or targeted therapies yet available, it also resulted in morgues and funeral homes being overwhelmed with the resultant need for refrigerated trucks to hold onto the bodies until they could be processed and these images were shown regularly on news updates about the pandemic. Of all the boroughs of NYC, the Bronx had the highest rate of hospitalization and deaths from COVID-19.

Prior to jumping into the study results, we do need to explore the concept of viral fitness. Viral fitness is actually a fairly complex construct that is influenced by many factors. Nevertheless, we can make it a simple concept by characterizing it as those characteristics that make the virus particularly successful in transmitting and infecting large portions of the population (so-called transmission fitness), as well as those characteristics that give the virus a transmission and infection advantage relative to other circulating viruses (so-called epidemiologic fitness).[ii]

Viruses that are predominantly spread by airborne transmission already have an advantage over those that are transmitted only through respiratory droplets and an even greater advantage over those that require prolonged, close proximity for transmission, because of the greater number of individuals that can be potential targets of infection at increasing distances away from the infected person. Transmission will also be promoted when large numbers of people are in that zone of infectivity in poorly ventilated space. Thus, you can already see that while we speak of viral fitness and generally think of fitness as intrinsic properties of the virus, human behavior can alter the transmission of even those viruses with high transmission fitness (a great example was in the winter of 2020, when our mitigation measures against COVID, markedly reduced circulation of RSV and influenza, so much so that, to my knowledge, it is the first time we eradicated a strain of influenza virus). Also, early in the pandemic, when people were staying at home more, avoiding large gatherings, maintaining physical distancing, and wearing masks, transmission of SARS-CoV-2 significantly decreased without affecting the biological fitness properties of the virus.

A virus requiring prolonged, close contact would not be on our list of potential pandemic candidates, because the requirement for prolonged, close contact does not contribute to transmission fitness. On the other hand, airborne viruses are clearly more concerning for potential pandemic spread for the reasons discussed above, as well as the fact that unlike large respiratory droplets that transmit shorter distances and land on people surfaces or objects relatively quickly (seconds), aerosols can remain suspended in air for up to an hour or more in poorly ventilated spaces. Just to make the point in a rather concrete way, and as a testament to the viral fitness and the threat of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, it has been estimated that the total mass of virions (virus particles) that caused infections throughout the world to create the COVID-19 pandemic would fit inside a typical soda can.[iii]

A major element of transmission fitness, especially after many in the population had a chance to become vaccinated or had been infected, or both, was the acquisition by the virus of immune escape capabilities. If you are a long-time follower of my blog, you will recall prior blog pieces in which we reviewed the immune system and its functioning. We discussed three main branches of the immune system: (1) the innate immune system; (2) the humoral immune system; and (3) the cellular immune system.

The key differences between the innate immune system and the other two are the more immediacy of response of the innate immune system and the fact that the innate immune system does not require prior exposure or priming to the virus before deploying its defensive measures against the virus. The innate immune system goes to work with the very first sensing of an invading virus, even one it has never seen before.

The humoral immune system is the part that makes antibodies. Unlike, the innate immune system, it can take 4 – 7 days to begin making antibodies to a newly recognized antigen/pathogen. The earliest type of antibodies made (IgM) are short-lived and typically, not the strongest (high affinity) nor the most effective (e.g., neutralizing in the case of some viruses). A class switch from IgM to IgG occurs, which peaks at around 7 – 10 days. IgG is higher affinity in binding to the antigen (the protein on the virus stimulating the immune reaction and lasts longer. Even after antibody levels have peaked, they continue to go through a process of maturation, in which the antibodies become finer tuned to the antigen resulting in higher affinity (better binding) antibodies.

On the other hand, if the person has already been vaccinated against the virus prior to infection, the antibody response can be shortened from 4 – 7 days to just 1 – 4 days. This is one of the main advantages of vaccination (I’ll have an entire blog post coming up on what we have learned about the vaccines), because antibodies work best to attach to the virus helping prevent it from infecting cells. Once the virus enters cells, the antibodies can’t access the virus. Thus, the earlier production of antibodies, the lower the amount of virus that gets into cells, the lower the viral load, and typically, the milder the illness. Further, instead of peaking at 7 – 10 days, if vaccinated, the peak occurs as early as 3 – 5 days.

Unfortunately, as the SARS-CoV-2 virus has mutated (as well as more recently undergone recombinations)[iv], it has developed an increasing ability to evade parts of the innate immune system and humoral immunity. Fortunately, it has not yet figured out how to evade the cellular immunity we have acquired. We’ll discuss the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccines in much more detail in upcoming blog posts as part of this series, and I will explain what would happen and what our response would need to be if the virus ever does figure out how to evade our cellular immunity.

If the SARS-CoV-2 virus were stopped from transmitting by the world’s collective non-pharmaceutical interventions or vaccines that could block transmission, or if the virus stopped transmitting and infecting people because of prior vaccination or infection and so-called herd immunity,[v] there would be the potential of SARS-CoV-2 being eliminated, but perhaps not eradicated (because of the large number of infected animals, some of which can transmit the virus to humans). Nevertheless, the fitness of the virus would dramatically diminish. However, none of this has occurred and the rapid rate of mutations (a trait of RNA viruses because of their error-prone polymerases [the enzyme that is responsible for assembling nucleotides into new copies of viral RNA]) has been accompanied by progressively greater degrees of immune evasion, which has in turn contributed to enhanced fitness.

Alright, back to the study. During the first three years, the Bronx experienced successive waves of infections. The variants circulating in the first year had the lowest viral fitness. Alpha and Iota caused the first two waves of the second year, and the viral fitness was identical for these two variants. Those first two waves of the second year were followed by Delta in the summer-to-fall, which demonstrated increased fitness and then by Omicron at the beginning of the third year, which demonstrated the greatest degree of fitness of all the prior variants.

Interestingly, Iota predominated in New York State even while Alpha dominated in most other parts of the country. This brings up another important point about mutations and fitness. Sometimes one fitness advantage comes at the expense of a different fitness feature. In this case, it appears that Alpha’s increased transmission due to increased ACE-2 receptor binding affinity came at the expense of immune evasion. Thus, it is possible that the population that had preexisting immunity from vaccination (which would have been very recent and thus, prior to significant waning) and/or prior infection (which had been quite high in the early months of the pandemic in the Bronx) did not provide a significantly susceptible population in the Bronx for Alpha, while Iota’s immune evasion allowed it a competitive advantage, despite less transmissibility.

Following the Alpha and Iota surges in New York, hospitalization rates due to Delta were lower than the average for the remainder of the country even though most evidence supports that Delta was more virulent, and when followed by Omicron, hospitalization rates were higher than the average for the remainder of the country.

It appears that Iota’s dominance in the Bronx was promoted by its earlier establishment in the Bronx compared to Alpha than occurred in other parts of the U.S. and its greater immune escape, whereas in most other parts of the country Alpha established itself first and had greater transmissibility and likelihood of causing infection due to its increase in ACE-2 receptor binding affinity.

Iota had more T-cell epitope diversity than Alpha (meaning that Iota had more antigens (proteins) that would be recognized by and stimulate a response from T-cells). T-cell activation is important in mounting a fast immune response and prevention of severe disease, including hospitalization. The significant underlying immunity from vaccination and/or infection from Iota with the development of neutralizing antibodies and priming of cellular immunity through the T-cell epitope diversity of Iota, likely protected the population from Delta’s most severe effects. Although Delta had increased virulence (ability to produce severe illness), it likely had less immune escape capabilities relative to Iota, accounting for the relatively lower hospitalization rates compared to other parts of the country where more people would have been infected with Alpha rather than Iota.

The higher hospitalization rate in the Bronx during Omicron relative to the rest of the country is more difficult to explain. Within the Bronx there was a significant correlation between Bronx Omicron cases and hospitalizations associated with the first introduction of SARS-CoV-2, suggesting similarities to a naive introduction, meaning that the prior Iota infection rate relative to Alpha appears to not have provided more significant immune protection against severe disease with Omicron as it did with Delta. The authors of the study comment little on this point. My own guess (I stress the word “guess”) is that there was less protection of the Bronx population perhaps due to a combination of factors – more time had passed since the first large wave of infections in March of 2020 that was earlier and larger than in most parts of the country and since initial vaccination (early 2021) with waning of neutralizing antibody protection; less severe infections with Delta might not have provided as strong of immune response and protection; and most likely, the fact that we know that there was significant antigenic shift with Omicron due to the striking number of mutations compared with earlier variants that likely provided Omicron with significantly increased immune escape.

Let’s look at another study, this one in a European country – Belgium.[vi] Before we jump in to the study results, it will be helpful to review a few key concepts and definitions again that otherwise may cause the reader confusion:

Endemic – The ongoing and persistent presence of a disease within a population over years.

Epidemic – Sudden and significant increase in the occurrence of a disease in a population and a geographical area associated with an outbreak if the illness is new to the area or a sudden and significant increase in the occurrence of disease over the baseline frequency of that disease if the disease is endemic to the area.

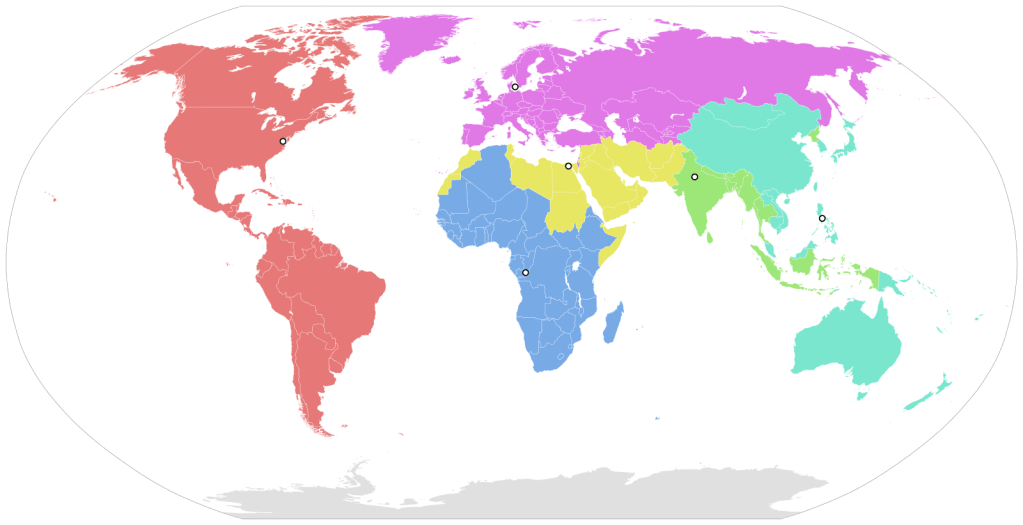

Pandemic – An epidemic that is world-wide, or at least involving three of the six WHO regions. (As a refresher, here is a map of the WHO regions):

Regions:

Africa (blue)

Americas (red)

Europe (purple)

Eastern Mediterranean (yellow)

South East Asia (green)

Western Pacific (cyan)

So, just to be clear in our concepts, a disease can be endemic (e.g., hepatitis C), and the epi curve would ordinarily show little variation along the x-axis (time). A disease can also be endemic such as influenza in which we have year-round cases, but at very low levels that then becomes epidemic when we enter the influenza season with one or more strains for which some of the population is susceptible (most importantly school-aged children) and transmit the infection to others causing a significant increase in cases and illness.

When SARS-CoV-2 first caused recognized outbreaks in the Hunan Providence of China (December 2019), this was an epidemic with a novel virus. By March of 2020, the WHO declared SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) a pandemic due to the ongoing transmission of the novel virus in multiple and ever-increasing numbers of WHO regions.

COVID-19 remains a pandemic due to the high ongoing transmission across the world, yet, one can also make the argument that it has become endemic given that it has persisted for four years now. Further, the waves or surges that we have often discussed are essentially epidemics within the pandemic as we see sudden significant increases in cases that last for months prior to receding. So, realize that these terms are not mutually exclusive. Think of endemic as the persistence of a disease over very long periods of time, unlike a food-poisoning outbreak that is generally contained within days or weeks. So, endemic correlates with duration. Think of epidemic as sudden increases in disease, so correlate epidemic with changes in magnitude of disease. Think of pandemic as the expanse of disease occurrence in terms of affecting multiple continents.

Okay. Back to the study. The authors define these terms, but the average reader is not likely to understand their definitions as well. No worries, because they are not in conflict with the definitions I provided above, they are just stated in more professional epidemiological language. So, I am going to provide those definitions from the studies so that you have them, but if they are not clear to you, go back to the definitions I provided you above and you’ll still understand the outcome of the study.

The authors state: “’infectious epidemic’ is characterised by a time trajectory of nonstationary variation in the number of new cases of infection in a cohort or in a population with three phases: increase, peak and decrease of incidence rate.” (See, I am guessing you like my definition better even though the authors and I are basically saying the same thing.) They further state how they are going to define peaks (epidemic waves) and the periods between peaks as follows: “the smoothed number of cases on peak day must be at least 30% above the number of cases two weeks before (peak day -14). When the interwave interval presented a period of fluctuations with multiple minimal values, the last prepeak minimal value and the first postpeak minimal value were taken as the starting date and ending date of successive waves. The interval period between two nonoverlapping epidemic waves – from the first postpeak minimal value of a wave to the last prepeak minimal value of the following wave – was defined as an interwave endemic period.” Now, if that made sense to you, wonderful. If not, don’t worry because I will show you pictures, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words.”

Here is Belgium’s COVID-19 epi curve for the first three years of the pandemic (March 2020 – January 2023):

Recall that epi curves plot the number of cases along the ordinate (y-axis) and the time along the abscissa (x-axis). For Belgium, you can see that 11 waves/surges/epidemics occurred during this time period.

We can make a number of interesting observations. First, with regard to the question we presented as to whether COVID-19 has become a seasonal virus, we see clear evidence that it is not. The waves’ start times ranged over the four seasons: 4 in winter (waves I, III, V, VI), 1 in spring (wave VII), 2 in summer (waves II, VIII), and 2 in autumn (waves IV, IX).

Also, just as we experienced in the U.S., each wave was associated with a different variant that became predominant.

It is also interesting to note that the first wave was not the highest one, just as was the case for most all other countries, and interestingly, just as was the case with the 1918-1919 Spanish Flu Pandemic. The 1918 Influenza pandemic had three waves and the first was not the highest in terms of cases, hospitalizations or deaths.

The authors use mathematical methods to study this data, but conclude:

“The lack of recurrence of the same VOC (variant of concern) during successive epidemic waves strongly suggests that a VOC has a limited persistence, disappearing from the population well before the expected proportion of the theoretical susceptible cohort being maximally infected.” In essence, “new VOCs replace old ones, even if the new VOC has a lower transmission rate than the preceding one.” This tells me that the variant replacing the prior one must be outcompeting it, or in other words, is more fit.

As I mentioned, we don’t have a good understanding of why this happens Note that in the first half of the pandemic, there were longer intervals between waves. However, right around the time that Omicron became dominant, the intervals shorten to the point that the next wave takes off before the prior wave has returned to baseline. There may be more than one factor at play. Early in the pandemic, many more people were exercising caution and implementing non-pharmaceutical measures. Studies also have shown that early variants gained fitness through increased transmissibility, while the mutation rate increased with time leading to fitness advantage through immune evasion. With fairly unmitigated spread by the time Omicron arrived, variants were quite divergent from the wild-type virus (original virus) and it appears that neutralizing antibody (humoral) immunity waned faster in the latter half of the pandemic.

In fact, if so-called herd immunity had developed by 2022 (you may recall Dr. Martin Makary’s bold prediction in a Wall Street Journal Opinion piece that we would achieve herd immunity by April of 2021[vii]) or even if there was long lasting immune protection from reinfection (there wasn’t), then we certainly would not have seen an epi curve like the one above where new waves occur successively without an intervening interval of time with cases returning to baseline.

While we are still learning and there remain many questions, here is where I think our current understanding is:

- SARS-CoV-2 infections and resulting COVID-19 are not seasonal. This could happen sometime in the future.

- Waves early on in the pandemic occurred with less frequency potentially because

- Greater use of non-pharmaceutical mitigation measures (distancing, masking, meeting outside, working from home, etc.)

- Slower rate of antigenic shift/drift (the first variant (D614G) had only a single nucleic acid substitution) and likelihood that antibodies generated from vaccines or infection were effective against subsequent variants for a longer period of time.

- Waves starting in January 2022 were averaging 28 nucleic acid changes per year, with progressively greater degrees of immune evasion likely limiting the duration of neutralizing antibody immunity.

Additional References:

- “Here’s why COVID-19 isn’t seasonal so far,” by Tina Hesman Saey. ScienceNews https://www.sciencenews.org/article/why-covid-not-seasonal. January 29, 2024.

- The Applied Genomic Epidemiology Handbook: A Practical Guide to Leveraging Pathogen Genomic Data in Public Health. Allison Black and Gytis Dudas, CRC Press, Computational Biology Series, 2024.

- Gordis Epidemiology, Celentano D., Moyses S., and Youssef, M. Elsevier, 7th ed., 2024.

[i] Community level variability in Bronx COVID-19 hospitalizations associated with differing viral variant adaptive strategies during the second year of the pandemic | medRxiv.

[ii] There are other aspects of fitness, e.g., replicative fitness – the efficiency of the virus in making viral progeny, however, for our purposes and our focus, references to fitness will concern transmission and epidemiologic fitness. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7102723/

[iii] Viral Fitness and Evolution: Population Dynamics and Adaptive Mechanisms, Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology vol. 439, Springer 2023. p. v.

[iv] There are many ways for changes to occur to the genetic material of the virus. Mutations are mot often where a misreading to the genetic material during the process of transcription results in a substitution of one nucleic acid for another. Mot of these are neutral in that they have no material effect on the virus functioning or fitness. Sometimes, these mutations, or a combination of mutations, may be deleterious interfering with the normal functions or the transmission fitness of the virus. In these cases, this new line of viral progeny will die out either because it cannot competitively transmit or because it cannot efficiently reproduce new virions. On occasion, a mutation or combination of mutations can improve viral fitness, improving transmission fitness by making the virus more transmissible (e.g., higher affinity binding to the ACE-2 receptor) – something that we saw dominate the first half of the pandemic- or by making the virus more immune evasive – something we have seen with the Omicron subvariants. Recombinations can occur when a person is infected with more than one variant and these variants exchange parts of their genetic material such that they contain a new genetic code made up partly of one variant and partly of the other.

[v] For an extensive discussion about herd immunity in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, see Preparing for the Next Global Outbreak: A Guide to Planning from the Schoolhouse to the White House, 2023, Johns Hopkins University Press. https://www.press.jhu.edu/books/browse-all?keyword=Pate%20and%20COVID-19%20.

[vi] Wording the trajectory of the three-year COVID-19 epidemic in a general population – Belgium | BMC Public Health | Full Text (biomedcentral.com).

[vii][vii] https://www.wsj.com/articles/well-have-herd-immunity-by-april-11613669731